Balancing Passion And Pragmatism: An Ikigai Approach To College And Career Choices

We are tempted to both give and receive bad advice when we wish something were true. I wish, for example, that college and career advice could be as simple as “follow your passions.” But it’s not.

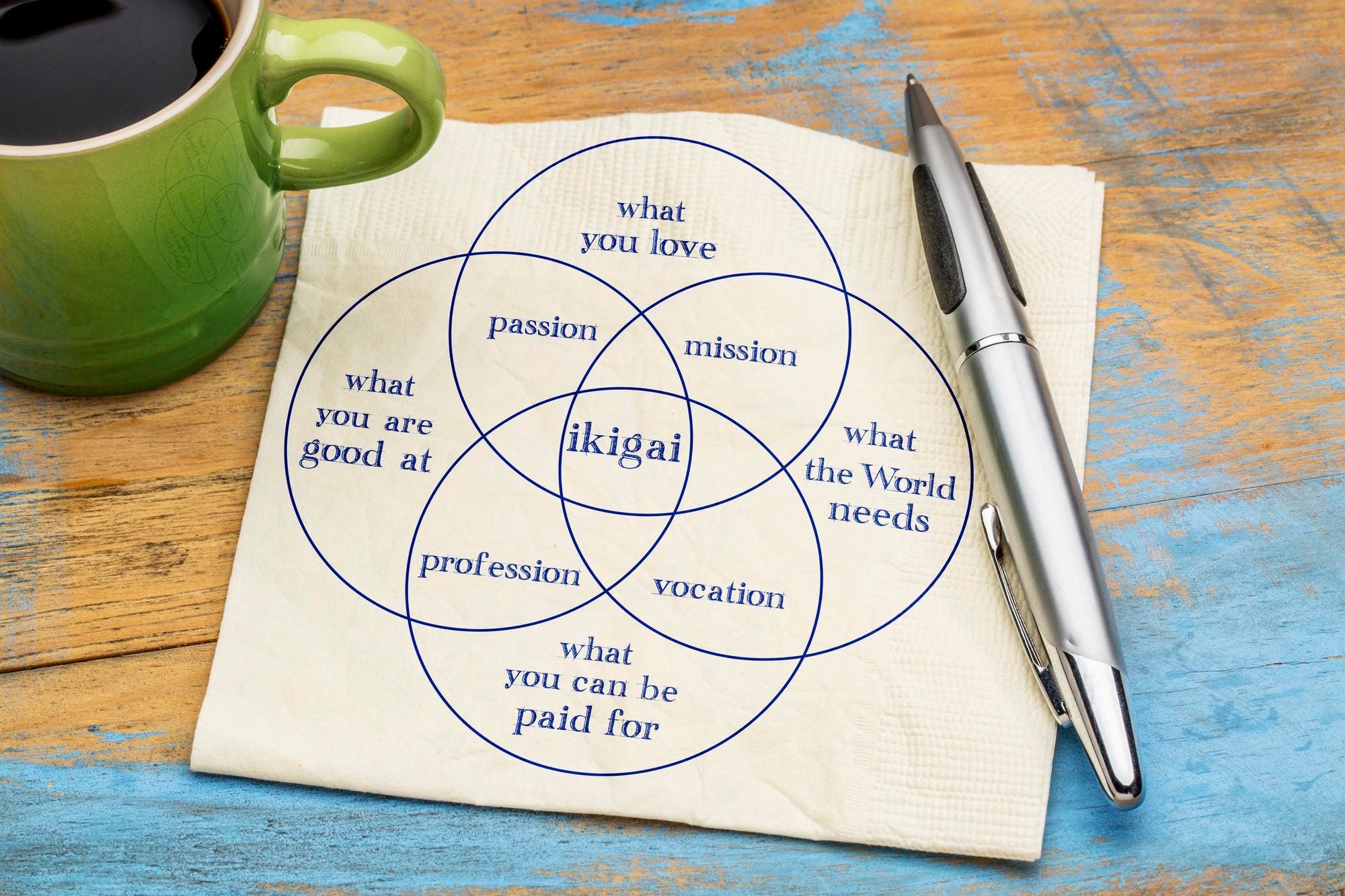

“Follow your passions” may be part of great college and career advice, but it falls woefully short on its own. In their Westernized adaptation of the deeply nuanced Japanese concept of ikigai, Hector Garcia and Francesc Miralles do an excellent job of showing us how and where our passions fit into these weighty decisions—and what additional factors need to be present.

In their book, Ikigai: The Japanese Secret To A Long And Healthy Life, they define ikigai “as the convergence of four primary elements”:

- What you love (your passion)

- What the world needs (your mission)

- What you are good at (your vocation)

- What you can get paid for (your profession)

What is your ikigai?

getty

As a financial advisor, I’d like to focus on the two big mistakes I’ve seen people make specifically related to the last piece of this ikigai puzzle—the finances—and how these mistakes can be avoided in college and career decisions.

1. In college decisions, students (and their parents) focus too little on the financial implications.

MORE FOR YOU

The commencement of college represents such a rich and vibrant time of life for so many that it has become unhelpfully romanticized. There is no denying that college is—or, at least, can be—so much more than a mere education. It is also an experience, an exploration in phased independence, that tends to grow (most of) us up into responsible adults. But part of that adulting is acknowledging that college is also a hyper-pragmatic ticket of entry

The romanticization of the experience part of college has led to this dreamy notion that it is priceless—that once you find the college of your dreams, the financial cost is relegated to virtual irrelevance. What’s especially interesting about this is that we don’t struggle to put a price tag on the other experiences we seek out in life. Vacations, concerts, movies, and dinners out are all experiences, too, but we’d never undertake these experiences without considering the cost.

Somehow, we’ve set a college education—the experience of your dreams—on such a singularly virtuous pedestal that any amount of expense is justified, even if it means incurring mounds of debt that will impair you from pursuing years of great experiences as a new graduate. And that’s why it’s imperative to acknowledge that college can, and I believe should, also be viewed as a value proposition. Here’s what I mean by that:

What you pay for college—the education, experience, exploration, and entry ticket to real life—should be directly connected to what that degree will entitle you to receive as compensation. This certainly doesn’t mean that everyone should follow a monolithic path toward the least expensive degree. Indeed, the world needs great neurosurgeons, so if you have the capacity and the love for that type of work, it could be worth it to pay the full price of admission to Johns Hopkins University. You may even justify racking up a mountain of debt for undergraduate and graduate school because you’ll be making enough money to pay it off quickly.

But the inverse is also true: If you are pursuing any number of incredible professions that the world desperately needs—teachers, social workers, civil servants, pastors, priests, and rabbis—that are also notorious for underpaying their workers, you must consider the financial implications.

While rules of thumb often fall short, one worthy of consideration here is that you shouldn’t take on more aggregate college debt than you expect to make in your first year’s salary. And even if you’re not taking on debt, the logic still holds, to tie your educational expenditures to the income you expect to earn.

But here’s the ironic twist.

2. In career decisions, people focus too much on the financial implications.

I’ve had the privilege of serving hundreds of families in some capacity throughout the course of my 27-year career (dang, I’m getting old!), and one the saddest things I’ve observed is when people get backed into a career corner because of the money.

Especially once you support a family and lifestyle (and have kids in college!), it is exceedingly difficult to change gears in pursuit of ikigai, simply because you can’t afford to. And irony on top of irony, this is a vicious cycle that often starts because people struggle to pay off their college loans!

The end result—even, if not especially, for the proverbial 1%—can be a race to retirement, where the work lacks the sense of meaning, purpose, and enjoyment that can turn a profession into a vocation.

Here’s the good news:

If you’ve missed the mark, there is still time. In Ikigai: The Japanese Art Of A Meaningful Life, author Yukari Mitsuhashi writes that, “Ikigai is not about seeking perfection or achievement, but about embracing the imperfections of life and finding beauty in them.”

Nobuo Suzuki instructs further in The Japan Times, “Ikigai is not something you find outside yourself; it’s about looking inside yourself. It’s about reflecting on what you like to do and what you’re good at.”

So, if you’re starting from scratch and building your plan for college—or just beginning to craft a meaningful career—I believe you could do no better than to return to the graphic above and ask yourself: What do I love doing, that I’m good at, that the world needs, and that could pay me enough to live the life I want?

But if you’re one of the majority reading this who are already well down the road of life and career, you might instead ask what calibrations you can make to the plan you’re already living out:

How could I enjoy the work I’m already doing more? What can I do to become even better at my chosen craft? Where might the need for my services be even greater?

And yes, because this final factor can erase the fulfillment of all the others when out of balance: How could I reduce or eliminate the strain of stretching finances by either making more money or spending less?

Comments are closed.